The Mental Gymnastics of “No ICE Raids on Farms”

The fuller story behind dairy immigration raids

This week, a neighbor sent me a story about an immigration raid at a dairy farm in Lovington, NM, asking me why she hasn’t seen any follow-up stories about the impacts these raids are having on farmers and consumers. You can read my response to her below, but first, I’m sharing an excerpt about how undocumented labor works in the dairy sector adapted from Farm (and Other F Words). In the end, I offer some last thoughts about the latest news and the broader situation of undocumented folks in the ag sector. I hope this provides some context for understanding what you see, and don’t, in news reporting about immigration in agriculture today.

The following excerpt has been edited for clarity, and sources have been removed for brevity. Please see the book for receipts.

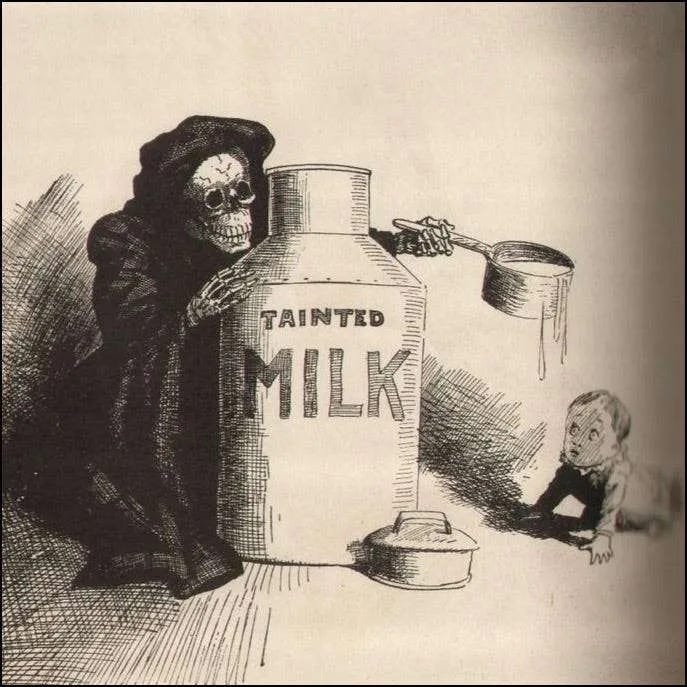

Milking the System

No industry is more dependent on an undocumented workforce than the US dairy sector. More than 80% of milk in the U.S. comes from farms that rely largely (or exclusively) on undocumented immigrants.

If you’re wondering how an entire multi-billion dollar industry that’s distributed across the country manages to pull off this massive violation of U.S. labor law, meet Max, a third-generation New York dairy farmer and self-described “kingpin” of farmworker trafficking.

Outside of Ithaca, New York, I found Max’s farm at the end of a two-lane road, past woods and open fields, a farmhouse, and a silo. I splashed down into the muddy parking lot outside his shop in the pouring rain and was greeted by a grinning man of about sixty. This was Max, who farms about 2,500 acres of farmland along with his more than eight hundred milk cows. He spoke to me on the record, but after conferring with farmworker advocates and legal advisors, I am using a pseudonym to protect the safety and privacy of undocumented people he employs.

When Max brought on his very first migrant workers from Central America in 2000, they came to his farm through a staffing service which passed through copies of their official documents. He found an attorney right away, hoping to get them on the path to a green card. But the lawyer knew immediately the documents were fake.

“She said ‘the only legal path you have to get legal workers in this country is the H-2A program, and these are not H-2A workers.’” Of course, the dairy sector doesn’t qualify for H-2A, because that program is explicitly for temporary, seasonal work, not year-round jobs like milking cows. But the lawyer instructed him to fill out their employment paperwork like the documents were real. And it worked, no one was the wiser.

“I kind of became the kingpin around here for workers,” he told me with a shrug. The workers he’d brought in were enthusiastic about bringing friends and family members to the farm, and so he was able to facilitate their journey.

“[My guys] said, ‘But it’s gonna cost $1,000 to get them here.’ That’s not much more than a plane ticket. So, they ask, ‘Can you lend us the money and take it out of their paycheck after they get here?’...That $1,000 goes to a coyote, who gets him across the border. And then they’ll show up here...in the middle of the night, with blacked-out windows and whatever.”

Until about 2012, Max says, that was how his farm got new migrant workers, and how he helped other farms in the area do the same. But then, he says, things changed.

“It very quickly went from $1,000 to a coyote to $7,500 to a drug lord because they could see this opportunity. [They realized] ‘there’s a whole human trafficking thing we’re missing here.’ So, they took over the getting illegal workers into the country, and the price went up.” Max tells me the story with a mix of exasperation and resignation, like a cook simply describing how the sausage gets made.

“$1,500 gets wired to a number. You have no idea. Goodbye $1,500...[That] buys you three chances across the border.” Luckily, Max says his guys have always gotten over during the first three tries. “The next $500 goes to the American rancher, who must have a turnstile or something, and charges $500 to these workers to walk across his ranch. They do it twenty at a time. So that’s the second payment.”

“After that, it’s typically, ‘We’re in Houston, wire another $1,000.’ ‘We’re in Atlanta, wire another $1,500.’ Pick a city anywhere, wire more. And this continues until you wire the last payment, and then you don’t hear anything for a couple days. And then you get a phone call that says your man is standing at the corner of 3rd and 42nd in New York City, and usually it’s in the middle of the night. Someone races four and a half hours down to New York City, looking for some poor guy standing on a corner with all of his belongings in a trash bag. So far, the last three guys we’ve gotten that way.”

[Men like Kilmar Abrego Garcia are on trial for allegedly taking part in this kind of activity– how many farmers have been similarly charged?]

As this route to obtaining workers has gotten more expensive, Max has moved away from it, instead offering his workers $500 cash to recruit workers from other farms in the area. But on a deeper level, hiring undocumented workers has left Max deeply conflicted.

He told me the story of a girl, the cousin of one of his workers, who had asked Max for a job. Upon finding out she was fourteen he categorically said ‘no,’ but his workers made a firm appeal. They explained that her father had been murdered back home and her sick mother needed her to earn money. If he didn’t hire her, they said, she’d go instead to the apple camps around Lake Ontario, where she’d live in isolated housing with almost exclusively adult men. Max eventually relented and said the girl ended up being a terrific asset to the farm, though she did not attend school— her work schedule at the farm didn’t allow it. She ended up marrying a local and starting a family. Now she’s an American citizen, and she and her husband both own their own businesses.

I spoke to immigration attorney Beth Lyon at Cornell University about the phenomenon of child farmworkers in American agriculture. The federal government has accounted for well over half a million children working on U.S. farms with as many as 100,000 likely undocumented. This number is inexact, in part because federal survey-takers have specifically avoided collecting data on minors under the age of fourteen, which is a problem because there is no minimum age for when children can work on farms with their parent’s permission. Max’s story exemplifies other reasons for the statistical murkiness, that either farmers or crew bosses don’t know the real ages of their young workers or don’t want to, and certainly don’t share them accurately. They usually can avoid doing so because farmworkers remain one of the most understudied groups, especially as compared to how much time and attention is spent studying farm business owners

I wasn’t able to speak to the workers on Max’s farm, but I was able to hear from other former and current dairy workers, including Crispin Hernandez, who has been a leading voice in advocating for stronger protections for New York farmworkers.

In our 2020 interview at his home, Crispin sat down with me over a Spanish-English language translation app to describe the three years he spent working on a dairy farm in the early twenty aughts, and the long-term damage the work did to his body. Crispin says he was fired when he attempted to organize workers on his employer's farm. Since then, he has labored instead to bring together and advocate for farmworkers on the state level as an organizer at the Worker’s Center of Central New York.

Crispin’s essential message is that farmworkers simply want to be treated with the same dignity and respect afforded to other workers in the U.S. Farmworkers want to get paid overtime when they work more than forty hours a week. They want to be able to rest so they don’t get hurt or over-exhausted doing highly physical tasks. They want to know they’re safe on the job, and that if they get hurt, they won’t be fired immediately and left crippled, penniless, and thousands of miles from their families.

I asked Crispin what he thinks of the kind of pushback I hear from farmers about the undue burden of labor costs on struggling farm businesses. The clincher of his response was “It’s not because they can’t afford to [pay overtime, etc.]. The reason is they don’t want to pay.”

Many farmers I’ve spoken to praise the efficiency of workers from Latin and Central America, as compared to their American counterparts. Maybe there would be enough local workers to staff dairy jobs, some farmers told me, but they certainly wouldn’t do it as well, or work as hard, as undocumented workers. This isn’t purely a difference of work ethics. One reason undocumented workers are incentivized to outwork their American peers is that they are, largely, at the mercy of their employer. Their residency status, their homes, and their ability to make money and achieve whatever goals drove them to make a dangerous international journey are all dependent on ensuring the farmer who brought them there remains pleased with their efforts. American workers have more protections, and act like it.

The cost of working in American agriculture for migrants is high. They may have access to more money than they would in comparable jobs in their home countries, but to access these jobs they have to cross the border illegally, often by putting themselves at the mercy of criminals, and then live and work at the whim of a farmer who they can only hope is a good boss and manager. Farm work, especially in the dairy sector, is also one of the most dangerous jobs in the country, and horrific incidents of workers drowning in manure lagoons or being crushed by equipment occur annually.

The labor problem for the dairy industry seems intractable. Farmers trying to make more money feel trapped between years of falling milk prices and calls for advocates like Crispin for more spending on labor. Part of the fundamental issue is that even as commodity milk prices have stagnated or fallen, production has continued to climb. These are self-reinforcing mechanisms—the lower the price, the more milk a farmer has to sell to earn the same revenue, so production keeps climbing, and oversupply has become endemic. This commodity milk spiral offers all the returns to maximum scale, efficiency, and low-cost production in a near perfect parallel to commodity grains (and there’s federal dairy payment programs too).

If the fundamental problem in dairy is that the price of commodity milk is too low, why don’t farmers sell milk some other way? A big part of the challenge in dairy is biology: cows have to be milked three times a day, and that milk needs to be transported, pasteurized, stored, and sold on a rapid and precise timeline, even if it’s going to be turned into cheese, yogurt, or whey protein. The marketing challenges of a quickly deteriorating product are significant, and dairy farmers often turn to established agricultural cooperatives or other commodity price purchasers to get their milk sold.

Without membership in a co-op, farmers would be on their own to either find a direct buyer for their milk or to build an independent business to process and sell it. But most farmers don’t get into dairy because they’re excited about milk marketing or logistics. Dairy farmers want to work with cows, so they have a strong incentive to stick with the co-op model, stomach the low commodity prices, and get undocumented workers by whatever means necessary.

I shared the above excerpt with my neighbor, as part of the explanation for why I wouldn’t expect many followup stories about dairy farm raids. This was the afterward:

I’ve covered the issue of undocumented labor in the dairy industry extensively, and I can tell you that more than 90% of all dairy workers in the U.S. are undocumented (some 500,000 people, by some measures), and farmers know that.

I don’t say this to vilify the farmers— they feel they can’t afford to pay what American workers would demand for the same work. This is not something that started during this administration, it’s been ongoing for decades, and dairy farmers often do not see another option.

Raids are certainly difficult for dairy businesses in the short term, but once the spotlight of media coverage is off them, they'll have better luck hiring a new batch of workers, who will present them with real (or real-looking) papers, even though all involved know they aren’t legitimate. It’s a don’t ask-don’t tell situation.

More than 90% of farmers across the country voted for Trump, a figure that holds in New Mexico too. I do not think these business owners will become outspoken critics of the actions of the administration anytime soon. They’ll let ICE have their “win” and after a few weeks, things will go back to business as usual.

As far as impacts on consumers, they’re minimal to non-existent. We produce vastly more milk in America than we consume (a fact that holds true across much of American agriculture). The price of milk (or other produce) is unlikely to be affected. In this one raid, about 30 workers were affected, and 11 taken into custody. But there are thousands of dairy workers in the state, and hundreds of thousands of cows. Not to mention that these are probably not the first raids these dairies have experienced. Dairies across the country have been getting periodically raided for years, so most know how to handle them and are not likely to go out of business as a result.

The true victims here aren’t farmers who depend on and hire (and sometimes exploit) undocumented migrants, or consumers. It’s the workers themselves and their communities. All 30+ people who were fired or taken into custody at this farm live in a small rural town in a poor state. That’s a lot of working-aged people who pay taxes, have families, shop at local businesses, pay rent, etc. that are now just gone. That’s kids going into foster care (or having their whole lives uprooted to be sent to a country they’ve probably never been to), rent going unpaid, businesses losing their customers, rural schools losing students, etc. And that’s to say nothing of the fear, suffering, and heartbreak that comes from being dragged from your workplace at gunpoint and secreted away by masked men to a prison (because that’s what a detention center is), and then sent to a country you haven’t been to in years (where you likely fear for your safety), with the whole life you’d worked so hard for left behind.

I think this is why people are protesting in the streets across this country right now— because these people aren’t violent criminals or drug dealers, they’re workers, parents, and community members who are keeping American farms, restaurants, and construction companies afloat through their willingness to work and their belief in the promises of our country.

This is the full picture that often gets left out of the 500 word print article or the punditry of cable news. But it also reveals why publications may not write follow-ups, because businesses and farms often stop answering calls from journalists immediately after raids. They don’t want to get on the administration's bad side by being too critical in the media. They just want to go back to flying under the radar so they can once again hire the undocumented workers they need.

In short, literally nothing is achieved in all of this but terror. There are no benefits to American workers, farmers, or consumers created by this mess. It is nothing more than an expensive exercise in torturing the most vulnerable people in our communities.

Finally, here are some parting thoughts I’ve been marinating on as the news has unfolded over the last several days, and what I think a “pause” on ICE raids on farms might mean for us all:

In much of my reporting on the dairy sector, I’ve been conflicted. Without question, all workers deserve dignity, legal protections, and to be safe from crime and abuse. But when asked what I think dairy farmers can or should do in light of the way their industry currently works— which few individual farmers have any control over— I genuinely don’t know.

It’s not that the U.S. dairy sector lacks capacity to act. In fact, as someone who’s stuck their nose in just about every agricultural sector in this country, I have consistently found the dairy sector to be one of the most professional, well-organized, and forward-thinking. You can’t run a dairy farm on nights and weekends, and it’s a bad hobby for a rich guy who just wants to cosplay as a farmer. That’s because dairy farming is hard. It’s a 24 hour/365 day business from day one, and the product is more perishable than most. All to say, I’ve met a lot of dairy farmers I not only really like, but also deeply, deeply respect as business people, managers, and stewards.

And despite that, dairy farms don’t have a lot of options here. Without H2A on the table, farmers only have two options for workers— undocumented people or Americans. I know dairymen who hire some American workers, and I can tell you that these folks often command $50+ an hour, and despite the price point, it’s difficult to hire Americans. There is just a lot of other jobs that are easier on the body, the sleep schedule, and at some level, the soul. To suddenly demand that dairy farms pay enough to fill hundreds of thousands of dairy jobs with American workers would likely be impossible given the commodity price of milk (pennies per gallon).

At many of the dairy farms I’ve visited, even undocumented workers are making $25 or $30 an hour, and in states like New York, competition to hire workers is fierce. If you don’t pay well enough, your guys might leave for the farm down the road. And tellingly, dairy jobs are often quite desirable for undocumented workers. $28/hour is way more than they can make elsewhere, and they can often get 60 hours a week or more. That’s a lot of money saved up or sent home to family. Workers want this. They are willing to take wild risks to come for these jobs, and they are human beings who deserve the right to make their own choices.

In these ways, the needs of U.S. dairy farmers and the desires of undocumented workers are often well aligned, and what’s more, I’ve met many farmers and farmworkers who just genuinely like one another. They have a lot in common— deep respect for hard work, care for animals and land, love for their families, and Christian values. Max (from the above excerpt) has taken multiple trips to visit his guys in their homes in Latin America, meeting their families and seeing the houses and farms they’ve built with the money they earned working on his farm. He showed me dozens of pictures hanging up around his office and on his phone of him and his guys. Frankly, I’ve seen love and care there, despite the wild power imbalance.

I talked to Max on his farm that day for hours. He was very open about his experiences and his concerns. He was also very clear about the future he wanted for his guys— citizenship. Max is no liberal, lefty, woke farmer. He’s a businessman and a registered Republican. But he also recognizes that as long as his guys aren’t safe in this country, neither is his business. He sees the value of treating them as human beings with intelligence, aptitudes, and lives worthy of dignity. He knows that it benefits him (and his bottom line) to see them that way. I mean, he’s never going to go to Washington and be the face of this position, but he supports it, even though he knows other farmers would crucify him for saying so.

Realistically, I don’t think farmers are going to lead the way on immigration reform, but I know there is a cohort of farmers, big and small, who would join a coalition demanding these outcomes. We’ve already seen the ag industry, from time to time, use its considerable power to try and advance ag immigration objectives, including a pathway to citizenship for workers. Of course, I also know it’s important to be watchful when ag advocates for change, and that it’s critical to monitor how the industry’s desired policies might further empower farmers to exploit. But that doesn’t mean the industry can’t be an ally in this work. And at times like these, we should be looking for allies wherever we can— even if the alliance is only temporary.

I’ve seen in the last few days that the president announced plans to “pause” ICE raids on farms, citing the outrage from farmers who’s businesses have been disrupted. I suppose we’ll see if the president is true to his words, though I’ve already seen reports that people in the administration have said, “no such policy change is planned.” I wonder though if this “pause” could prove even more dangerous for undocumented farmworkers than the current “across the board” deportation policy.

Imagine this. I’m an undocumented worker at a dairy farm. My boss knows I’m undocumented. Trump has “paused” raids on workplaces like mine, but the moment I lose this job, I will be targeted for deportation. Heck, my boss might be on the phone to immigration before I make it my car. If this power to have and dispose of workers is suddenly in the hands of farmers in a more formal way than ever before, like a sword of Damocles hanging over workers’ heads– do you think I will ever say no to anything my boss asks of me? That’s why this “pause” could make it more likely that workers are forced into more grueling work schedules, suffer more wage theft, work more while sick (for example, with H5N1, the deadly bird flu that’s been detected in dairy cows and dairy workers in the U.S.), and overall experience more dangerous and shitty conditions. I’d also expect more workplace assaults, more sexual harassment and abuse, more deaths on the job, and more pandemic-level threats related to animal-borne diseases.

For me, the takeaway is this. The situation our country is facing right now isn’t about threats to farms or consumers directly— but at the same time, it is. Because farmworkers really, really are part of the foundation of our nation. Our safety, health, and liberation, and that of our families and communities, is directly tied up with theirs. “Pausing” ICE raids on farms is not a solution, and our response should not be to sigh with relief. The only real solution for farmworkers, for farmers, and for all of us, is far more fundamental change in the American immigration system. It’s a pathway to citizenship for the people who feed us.

And until migrant farmworkers are free and safe to work with dignity, none of us ever will be.

I'm from a farm family. In Canada we have the Temporary Foreign Worker program for jobs unable to be filled by Canadians. In Home Care that could be a Punjabi speaking relative for a disabled senior. They might end up working 24/7 off the record, but are supposed to follow labour standards.

That sounds similar to dairy industry staffing needs in that they are 24/7. Shifts, overtime, vacation etc. would need organizing. And 25 to 30 bucks an hour is something that may have appeal to uneducated non-english manual labour workers. If the workers could communicate with each other through a labour organization, it would encourage good behavior amongst management, as you said.

As someone who thinks a LOT about the "food supply" and the coming climate disruptions to agricultural*. I found your piece both interesting and informative.

I would never have guessed that there might be 500,000 undocumented workers involved in producing the milk I put on my daily oatmeal. I find it appalling that so little has changed from the days of Steinbeck's "Grapes of Wrath".

*See the report : Warmer planet will trigger increased farm losses (https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2024/01/report-warmer-planet-will-trigger-increased-farm-losses)

"This report involving Cornell University researchers indicates that for every 1°C of warming, yields of major crops like corn, soybeans, and wheat decrease by 16% to 20%. This study, which was a collaboration with other institutions and reported by the Cornell Chronicle, highlights the significant negative impact of rising global temperatures on agricultural productivity."