“Rain Follows the Plow” is Dead, Long Live “Rain Follows the Cow”

I was visiting a farm in the Southeast a couple of years ago, and our visit happened to overlap with another guys, who’d come (I guess?) to pitch the well-heeled owners on his amazing regenerative ag breakthrough.

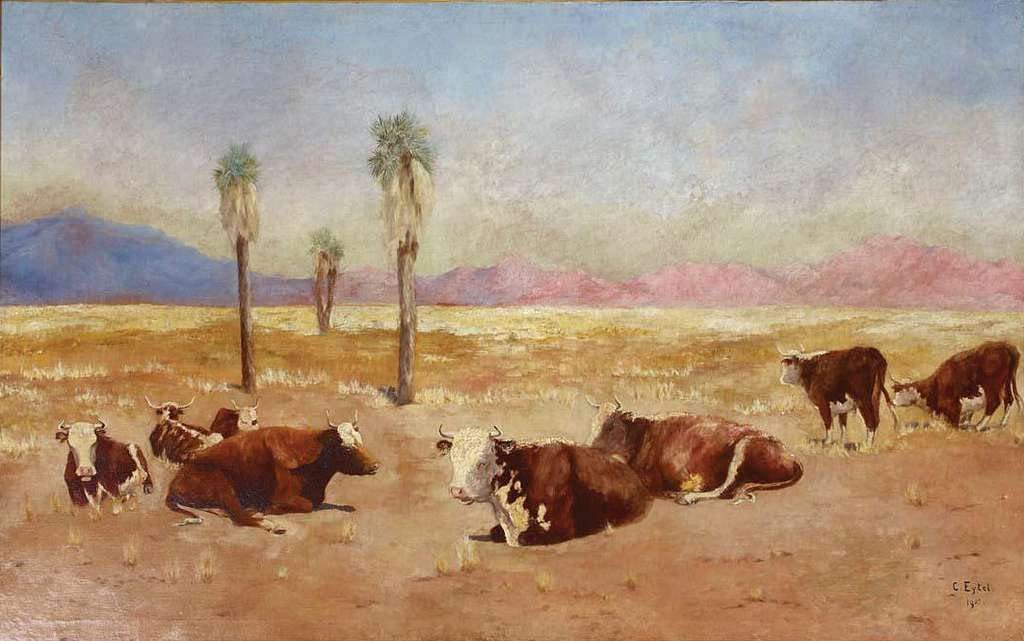

He was telling a story about the Chihuahua Desert over lunch that caught my attention. He was talking about a ranch he worked for in Mexico, and how they’d come in with a herd of cattle and grazed them out on the desert plains. The miracle was that apparently, within the course of a year or two, there was a demonstrable increase in both edible plant growth in the areas where the cows “grazed” and in the amount of precipitation. This was a jaw-dropping finding, and everyone around the table was, predictably, quite impressed.

“We’ve got projects now in the UAE,” the man boasted. “With our regenerative grazing management methods, we’re literally transforming deserts into grasslands, turning them into good pastures for raising cattle. Turning wasteland into productive land.”

The point of the story was to encourage these farm owners, who were deeply dedicated to the idea of regeneration through pastured livestock, to invest in this and other grazing projects, to the tune of a couple million bucks.

I was visiting this farm with a biogeochemist friend of mine— a soil science and ecology expert. She had some questions, but the guy was in a rush and didn’t have time to answer any. But she and I talked a lot about this as we drove away from the farm. Okay, it was mainly me asking her how that would even be possible.

The short answer– it’s not.

___

This man is hardly the first to promise that the right agricultural practice could transform a desert into a paradise.

In fact, in the late 19th and early 20th century, there was a very popular agricultural theory that boiled down, essentially, to “rain follows the plow.” This was not an old wives tale, it was a scientific hypothesis, and a very popular one. The idea was that as farmers turn over soil, the action releases soil moisture into the local atmosphere, which would in turn lead to an increase in rainfall, which would help plants grow, and then plants transpire, and that also can encourage rainfall, and on and on. It was the identification of a virtuous cycle, one that meant that as American farmers ventured out over the plains and prairies towards California, they could bring the rain with them wherever they went simply by working the land.

Maybe to our modern ears, this all seems a little quaint, a heavy dose of wishful thinking mixed with a splash of manifest destiny. But back then, this was a new and fabulous idea that people really took to heart. It helped poor folks with homesteads in Western Kansas and the panhandle of Texas believe that, even though their land seemed barren and bone dry, it wouldn’t be that way for long. And it helped the government justify not expanding the size of homestead allotments– after all, 160 acres was sufficient in Iowa, and Western Oklahoma would be just like Iowa, if those lazy homesteaders would just put their backs into it.

The thing that the “rain follows the plow” pushers wouldn’t or couldn’t acknowledge was that the high Western Great Plains were not like Iowa. Some people knew this. John Wesley Powell very famously told Congress about the Great American Desert West of the 100th parallel, and his crusade to establish Western states along watershed boundaries very famously ruined his career.

“No, no,” the rain-follows-the-plowers said to Powell. “It’s a desert right now. But give smart people a little time to work their magic, and we’ll be farming wheat and tomatoes from Brownsville to Billings. No need to align communities along watersheds. Farmers will be making their own water from the dirt.”

___

The problem, my very smart friend told me, is that you simply cannot make something from nothing. What the regenerative grazing guy was selling was that cattle, apparently with their hooves and dung alone, could fundamentally alter the soil chemistry, plant biome, and climate, and all in the course of a year or two. But how?

For one, there’s the problem of water. Cattle need water, and water does not come from nowhere, especially in a desert. We supposed that drilling a wind-powered well would not necessarily disrupt your claims of this being pristinely regenerative beef, but if it’s being trucked in from somewhere else, that would certainly raise some questions. On the other hand is the question of feeding these beef animals. They need a lot of calories daily and will gain best when it’s a balanced diet of forages. This is not available in the desert (that's why ungulates generally don’t live in deserts!), so these people must be trucking in massive amounts of hay and alfalfa to keep these animals healthy and growing day to day.

Given all of this, how might these cattle be affecting the soil? Well, they’re still pooping and peeing, expelling all that imported water and plant material. That would probably have some impact on the soil (though might it be more efficient to simply dump the water and alfalfa directly on the ground, and skip the middle cow, so to speak?). But for this defecation to be having any kind of widespread impact over an area large enough to influence rainfall, these animals would really have to be moving around. If they’re moving around, then you’d have to be trucking water to them (you can’t move a well, of course).

Then there’s the simple question of the heat. Cattle, especially beef breeds, tend to be built for cold climates, not hot ones. High temperatures, even for relatively short periods, can be deadly. When cattle are stuck outside for months at a time in the blinding sun and 80, 90, and 100+ degree desert heat, they certainly aren’t going to be walking around, turning dirt and fecal matter under hoof, and eating desert plants. They’re going to try to wallow in whatever water is around (cattle are the descendants of European swamp-dwellers, after all). That or they will lie in the shade, likely in severe discomfort.

As our discussion continued, the reality became clear. The idea that cattle, especially “regeneratively grazed cattle” could literally turn deserts into grasslands is a fabulous promise. It’s down right magical. And in our age of climate anxiety and food system angst, I get the draw. But it only takes a few minutes of critical thought to realize that the thing about water is, you can’t create it from nothing.

We have the idiom “to squeeze blood from a stone,” and I think it could just as easily be “farm water from a desert.” Whether that desert is the high plains of the early 1900s or the modern deserts of the world, water cannot be conjured where it simply does not exist. We have not bred a species of magical “regenerative” cattle that can do this thing. Cattle are just cattle. Farmers are just farmers. Ranchers are just ranchers.

And perhaps most importantly of all, deserts are deserts. They are not, in most cases, just unfortunate spots of land that have fallen on hard times and need a hand up. They are what they are. They have their own climates, their own ecosystems, their own precious species and biomes. Deserts are not trying to be something else. Not every inch of the Earth’s surface means (or needs) to be farmed, and a place is not a “waste” simply because it’s not being used to make money. Deserts are sacred places with their own roles and destinies.

You’d think we’d have a little more care and respect for deserts, given that deserts are the places where humans have done some of their finest work. We built many of our first civilizations in deserts. We’ve wandered in deserts to conjure visions and to have epiphanies. We admire the harshness and the beauty, their wonder and mystery.

You’d think given our history with deserts, that it wouldn’t be so hard to acknowledge that these landscapes don’t need magic water, conjured with a plow or a cow. Deserts have their own magic– a magic of salt and sand, of cactus and cottontail, of sun and sidewinder. Deserts do not need to be fixed or reclaimed. They are not lost or broken.

___

So if someone asks for your money to help their project of “reclaiming” desert with regenerative grazing, maybe give it a good thought first, about where the promised water will actually come from, for one. Will it be conjured from non-existent soil moisture, or summoned from non-existent weather patterns? Will it be sucked from a fossil reservoir underground, used until it runs dry and the desert returns? Will it be trucked or piped in from some distant landscape, robbing some other place, plants, and animals of the moisture they need to survive? And then think about what the physical reality for that land has been for the years, decades, and centuries before the current owner got there. And then, with clear eyes, decide whether cattle, a non-native grazer on the North American landscape, are really the right animal to be “restoring” or “regenerating“ that place anyway.

If the person pushes (and sales people always do), maybe tell them the story about what happened to the rain-follows-the-plowers. They won the day in their time, their narrative was the dominant one, and their conclusions helped shape the settlement of the Great Plains. And this settlement style, in large part, caused the Dust Bowl. Because it turns out, the more you turn the soil over and over, searching for moisture that simply isn’t there, the more vulnerable it becomes to blowing away. It’s not hard to imagine that the more hot, heavy-hoofed cattle we put out on the fragile surface of our high and low deserts, a cataclysm of similar magnitude could be created.

And you know what, I don’t think anyone deserves that. Not the people who see the desert as sacred, not the desert’s neighbors who will suffer for its decline, not the ranchers and farmers who want to believe in these promises. Not even the cattle. No one deserves this fate.

To learn more about “rain follows the plow,” the Dust Bowl, and how they both contributed to modern farm policy, take a listen to the latest episode of my limited series about American farmland— The Only Thing That Lasts. Available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Yeah, regenerative grazing, whatever that is, won't turn a dessert into a garden. There's as much snake oil in the ag world as in any other industry. But careful livestock grazing, along with cover crops and other soil health practices, can return farmland that's been row cropped to barrenness back to a more robust productive state. Flooding becomes less frequent and severe, and drought is more easily managed, all while native fertility increases. So, I hope readers of your piece won't confuse intentional practices that really do benefit soil health with nonsensical claims of turning the dessert into paradise.

Thank you for writing about this so clearly, in a way that the obvious questions you raised in your narrative about where the hell is the water going to come from, both for the plow or the cow, should have made the proponent of these theories wary about their outcomes. Nonetheless, it seems to me that these approaches to agriculture were, or have been, taken as direct implementations of some sort scientific principle or hypothesis that predicted their success.

My question is, when you write about the plow that "This...was a scientific hypothesis, and a very popular one.”, what were the primary sources (i.e., scientific research, publications, etc.) for this scientific hypothesis?