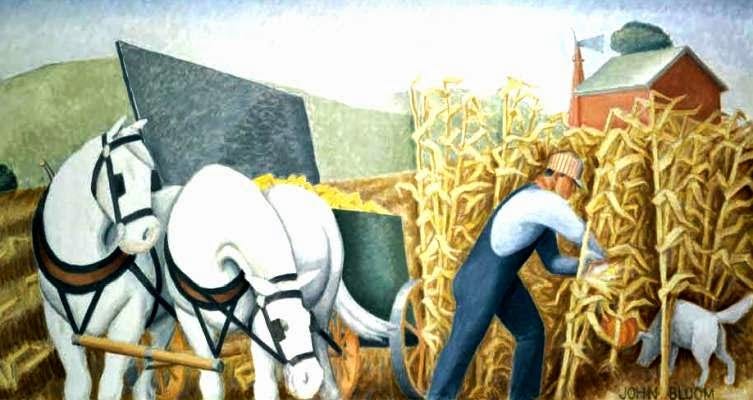

Most people don’t realize how sharp the leaves of a dried corn plant can be. Imagine a pointy tip of paper that is at once flimsy and brittle, feather-light to the touch but also supernaturally adept at connecting with the skin at just the right angle to apply breath-sucking cuts to exposed skin.

You’re liable to get these cuts just walking through a corn field near harvest time if you're not wearing a long sleeve shirt and pants. Now imagine that rather than just passing through a field, it was your job to move systematically from plant to plant, locating each individual cob, removing it from the stalk, and then removing the husk.

“That was true hell. Although we wore cotton gloves and covered our forearms with sleeves torn from old sweaters, the husks still managed to cut and scrape until our hands and arms were raw and bleeding.” This is a direct quote from Norman Borlaug, the famed plant breeder of the green revolution, and in his boyhood, a farmworker on his dad’s Iowa corn operation.

I like to trot this quote out sometimes, especially when people seem to be getting excited about “our grandparents farms.” I mean, I get it. Nostalgia always hits. I’m not saying there weren’t upsides to the simpler life people lived back then. But I think one of the things people forget when they romanticize farm life of the past is that farming, for the vast majority of human history, was little more than a subsistence activity, and an incredibly laborious one at that. Sure, there have always been a few gentlemen planters and cattle barons, but overall, most farmers have been a poor and meager lot.

The physical pain and sacrifice of Borlaug’s childhood was, without a doubt, a motivator for the man to spend his life creating ultra-high efficient crops. Though he loved his family, was enamored with plants, and even at times saw farmwork as an interesting personal challenge, I don’t think he found the idea of romantic, agrarian poverty very charming at all. For a kid like him, fascinated by science, all he wanted was to go to the local public high school. But instead he spent two months of the year (October and November) fighting corn stalks with knives in their hands to loose their cobs, often spending the day half stooped, picking up windblown plants. Most nights he was in so much pain it was hard for him to sleep.

Today, there is very little labor involved in corn production, and I think Norman Borlaug and his classmates would be very happy about that. Wheat threshing and cotton picking too are no longer done by hand, but by enormous machines, many complete with air conditioning, cupholders, even mini-fridges.

But there is plenty of farm labor still happening in America. Workers still pick tomatoes and strawberries, prune apple and pear trees, plant almond and pistachio orchards. Despite ultra-high tech milking parlors, dairies still need workers to push cattle in and out of barns, attach and detach milking equipment, and check for problems. Workers herd sheep and muck stables, pack produce in the field, irrigate, drive equipment, and spray chemicals. Millions of workers are still involved in planting America’s farms, raising its livestock, and bringing in its harvests.

____

Though Norman’s old gig might not really exist anymore, many of the jobs in ag that remain still suck.

Take fresh market tomatoes. These sensitive fruits are picked when green, but not all the fruit on a given plant will be at the right stage of growth. To harvest them then, workers approach a plant, bend down, move the leaves, identify the harvestable fruits, and then pull them from the vine and place them in a plastic tub between their feet. It may well take several plants to fill the bucket up, and so the worker must move this bucket down the row, until it weighs approximately 35 pounds. Once it’s full, the worker stands, hauls the bucket onto their shoulder, and then is off to the loading truck. At the truck, they hand or toss the bucket up to a loader, who records their bucket, or perhaps gives them a token they must hold onto until the end of the day (to keep tally of their work).

The recording or tokens are important because these workers are only paid by the bucket– a few quarters for each. That means that all of the above steps not only have to be carried out over and over again for hours on end, but that they are best carried out at maximum speed if you want to make a meaningful wage for a day's work. That means running, jumping, heaving, and throwing heavy and ungainly buckets around a field, often in blistering heat and sun, an effort that leaves workers incredibly vulnerable to injury, dehydration, even life-threatening events. And in exchange, workers often pocket little more than minimum wage.

This is just one crop, and every one is different. But a few things remain consistent. Farm work is usually a time-sensitive matter. Fruits and vegetables must be harvested when they’re ripe, cows must be milked promptly, livestock fed. That means long and often rigid hours. Otherwise it’s famine– seasonal harvest work dries up, and so do the jobs, forcing workers to either migrate throughout the year to follow the harvest or else find some other way to pay rent and buy food.

The farm labor that hasn’t yet been taken over by a machine, the work that’s left to be done today, is usually in some way at least, difficult. If it weren’t, a machine would be doing it. Identifying a ripe apple and pulling it off a tree while standing on a ladder is a challenging task. Moving living, hoofed, grumpy cows around a dairy can be tricky, and can result in everything from pink eye to broken ribs. Operating equipment in a crop field where millions of dollars of capital and revenue are just feet from the tires you’re steering is skilled work. These jobs are important, and for many of them, there is no nearly-there innovation that’s going to relieve the pressure. These jobs need workers.

____

There’s an old saying in agriculture, that there’s no better fertilizer than the farmer’s shadow. We know, and have known for a long time, that thoughtful care and management aren’t a nice-to-have on the farm, they are actually worth having. Like there's a demonstrable financial return in the form of reduced costs and increased revenue that can be attributed to having more human eyes on the crop, on feed, on irrigation, on soil, etc.

Farmworkers, too, have farmers’ shadows. Farmworkers in America, especially migrant farmworkers, often have significant experience in agricultural production. Many come to the states from their own farms, laboring in California or Florida or Michigan in the off-season, or for a few years, long enough to save up a nest egg for their own place back home. Even if they don’t, many farmworkers have been working on farms in the U.S. long enough to have gained valuable skills, often across a range of crops. Therefore farmworkers often don’t need training to be able to identify problems, to make corrections, or to demonstrate the same thoughtful care and management they might use on their own farms. What they need is permission and power to take action, incentive to be on the lookout for improvements, and a job that doesn’t suck so much that they couldn’t care less either way.

This, however, is not usually how farms and farmers thinks about labor. Farmworkers are not usually seen as a well of untapped potential– more often they’re a line item on the farm’s balance sheet that needs to be minimized. That’s why there’s been so much focus for so long on eliminating farm work altogether. What’s the point in eliminating some of the labor, say, by making the job easier for workers, and thus making them more productive and efficient? The preference instead is to make workers altogether obsolete, even if the technology that would be required to achieve this is a long way off, and labor-enhancing technologies are much closer.

The holy grail of labor replacing technologies is, of course, the mechanical (or better yet, autonomous!) harvester. Most of these tools, be there for tomatoes, strawberries, pears, or grapes, are envisioned as robots, some miraculous tool that can move at speed, plucking delicate fruit from tiny, ground-hugging vines and the highest branches of trees, depositing them safely in a collection bin, and doing it all before the crop advances past the peak of freshness, and at a reasonable price point. For most major fresh market crops, some version of this robotic harvester has been “nearly ready” for decades. Scientists, technologists, and startups have been “on the cusp” of solving this extraordinarily difficult challenge with its many stringent speed and cost constraints multiple times, and many investors, industry groups, and even farmers themselves have backed various attempts. Few to none are commercially viable at this point.

The simple reality is, humans have had 100,000 years to refine our fruit-observing and -picking skills. Robots, well, they have a long way to go to catch up.

All this to say, the most practical path forward is at this time is clear. Farm work sucks. We know it sucks. It has sucked for a long time, at least since people were slicing up their arms with corn stalks and their legs on cotton brambles. On the other hand, the machines are not ready to take over. They need years at least, maybe decades, before any kind of wholesale replacement of farm labor might even be possible, and even then, it will only be in some industries and for some tasks. Robots, at least for now, do not have farmers’ shadows like farm workers do. And workers can be a source of value to a farm operation, under the right conditions.

Therefore, the only rational thing to do is stop putting all the eggs in the “labor-replacing robot” basket, and start investing in tools, technologies, management practices, and maybe even policies and regulations, that improve the jobs and lives of farmworkers.

____

Among the farmworkers I’ve had the pleasure to meet, many of them liked their work. I’ve certainly met some who hated it too, who felt abused, taken advantage of, harassed, and harmed, and those experiences are too common. But I’ve met many who like the effort and the challenge of it, the movement of their body, the being outside. Many of them like farm work because they like farming, because they are farmers, whether or not they own the land they currently work. But whether a given worker likes or hates their work is besides the point. People have all kinds of jobs they love and hate. Surely some fast food workers love their job, and some high powered lawyers and doctors hate theirs. Jobs are jobs, in our capitalist society, we need them to survive.

There’s a talking point across the political spectrum, too, about the dignity of work. Many farmworkers I’ve met have told me something like that about their work. That liking or disliking it is besides the point. They need to work, and so they do this work to the best of their ability, and they are happy for the opportunity. These farmers work, and what they deserve in return is the tools to do their jobs well, and to continue to do their jobs well as long as they want or need to. They deserve safe conditions and a living wage, not broken bodies and no legal status.

Farm work has always been a sacrificial enterprise, but at least in Norman Borlaug’s day, he was harvesting his father’s corn, sacrificing his arms, hands, and back to bring in the crop on land that he might inherit one day. Today’s farmworkers are not repaid in kind for the sacrifices they make of their bodies. We should give workers land, or enough wages to buy land themselves (or a path to citizenship, a path to an ownership claim over the land called “USA”). In the meantime, we could at least invest in limiting the sacrifice demanded of them. Enhancing labor, rather than replacing it. Protecting and investing in workers, rather than replacing them. This is a path towards a more safe and just food system, not just for eaters or farmers, but for all the people who make our diets, and society, possible.

Yep, let's make farm labor less onerous. Let's direct investment to innovation that will support farm labor. Tractors, harvesters, combines and a lot of other tools have made farm life a lot better. Let's also pay farm laborers better and offer them benefits many office workers take for granted.

Consumers will have to pay more for food. And we'll need to agree on some forcing mechanism (unions?, regulations?, shame?) so that higher prices benefit those doing the labor instead of those who administer the business or provide capital, no matter what part of the food supply chain they occupy. But those are problems that all industries need to solve, not just agriculture.

It's not realistic to hope that farm labor will eventually be able to own enough land to farm by saving their farm wages. I don't think that has ever worked here or anywhere else. Farm workers are labor in a manufacturing plant called a farm. Other than its episodic nature and relaxed OSHA and other regs, it's not really different from other manufacturing jobs. Who expects an auto work to own their own assembly line?

But the flip side is maybe it's time for the pendulum to swing back to labor receiving a bigger piece of the pie from where it's gotten today.

Love your column. I really respect you for including the farm workers’ perspective. One thing I see missing from the national conversation on farming is how we create a system where those farm farmland ownership can transition to the farm workers. Would love to hear your thoughts!