But Isn't Animal Feed Part of the Food System?

Addressing the Livestock (Feed) in the Room

Programming note: This newsletter has been completely free for years, and I plan to keep it that way for the foreseeable future. But since so many have asked to support my work in recent months, and because stories like today’s take a ton of time assemble, I’m turning on paid subscriptions. If you’re interested and able to invest in my work, now you can. There’s a lot more like this (and even more involved work and big announcements!) coming up soon. Thank you in advance, and if you have any questions, don’t hesitate to reach out.

Over the last three weeks, I’ve received many variations on this question:

If most of our corn is used for livestock feed, doesn't that livestock become meat we eat? If so, couldn't consumer facing brands like a McDonalds have an impact, say by requiring more grass fed beef vs. corn fed?

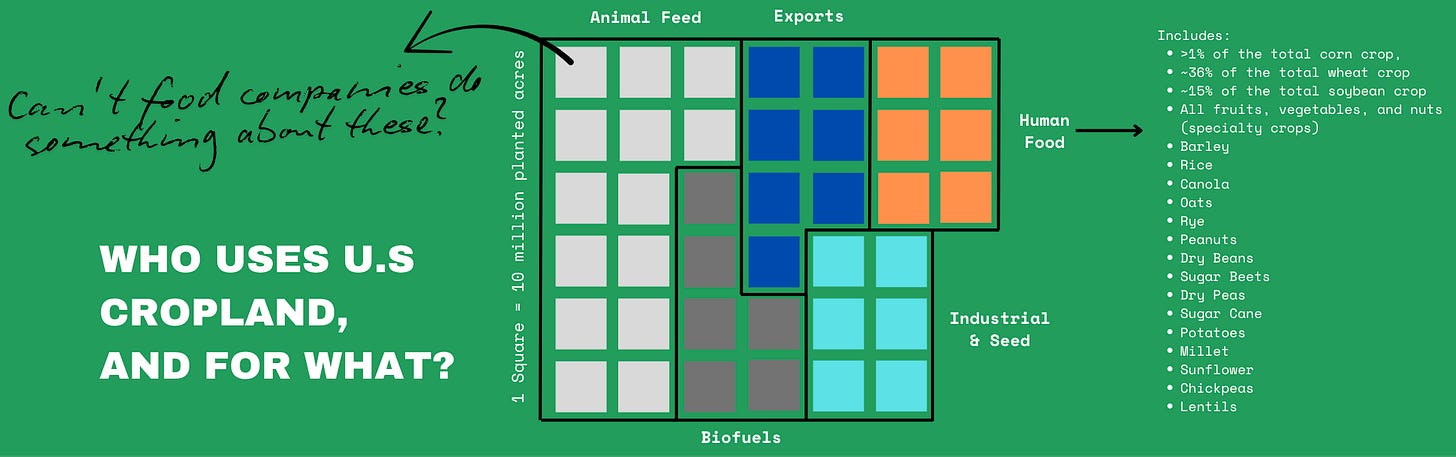

In other words, aren’t “Human Food” acres and “Animal Feed” acres farmland acres where food companies could have an impact?

This is a great question-- but one that’s deceptively hard to answer succinctly. The shortest possible version is that yes, animal feed does go into the food we eat, but that doesn’t mean that food companies have much (or any) control over it.

To explain why, I’m going to unpack four questions that together will offer the insight you’re looking for:

What crops go into the livestock feed that becomes animal protein?

What incentive do consumer-facing food companies (like McDonalds) have to impact what their meat eats?

What power do these food companies have to impact what their meat eats?

Isn’t grass-fed the right alternative?

One quick note: I want to re-emphasize the original point I was making, which is that consumer-facing food companies and brands do not have the right leverage to drive large-scale change on American farmland. I am not arguing that food companies have no power to make change in the systems in which they participate (they do) or that they should not be held accountable for their role in harming environments or human health (they should). I am just arguing that we should not expect recognizable food brands to lead the charge in changing the farm landscape (not least because, once again, The Food System and the Farm System Are Not The Same).

Okay, now onto our questions.

What crops go into the livestock feed that becomes animal protein?

To understand the influence food companies have on the world of animal feed, first we need to know what it is that animals actually eat.

If you were hoping for a fun spin on the above graphic, I’m sorry to disappoint. But I have a good reason. It’s because the world of “animal feed” is easily one of least transparent and most difficult to predict parts of American agriculture, mostly because what animals eat varies a lot— by animal, product, geography, and season.

Now, you might be thinking, “Even I know what cows eat. Hay and corn.” And, well, maybe! But they might also eat wheat, sorghum, soybean or canola meal, oats, dried distiller grain, almond hulls, citrus pulp, cough drops, corn silage, alfalfa, or even native vegetation. And even over the course of a cow’s life, this diet is likely to change. After all, is it a dairy cow or beef cattle? A calf? A steer? A milker? Are these cattle on pasture, or are they confined? Are they in Southeastern New Mexico or Vermont? Is it February or July? How’s this year’s wheat crop? What’s the current margin on biodiesel? The answers to these and countless other questions can influence animal feed mixes, for cattle and other livestock as well. This is in large part because raising livestock for commodity protein is a low-margin business, and for animal-raisers, sourcing the cheapest feed that meets their need is often the difference between selling at a profit or a loss.

This dietary flexibility matters to even the most committed and well-capitalized food companies. First, it means that it’s hard to nail down which acres, or even how many acres, are grown specifically for animal feed, and what, specifically, is grown on them.* If this information were easier to get at, maybe food companies could-- rather than work through their long and often opaque supply chains-- make an end run around the chain and intervene directly on the relevant acres instead. But because of the extraordinary variability in how farmers source feed, this can be wildly difficult to do in a meaningful way.**

It also means that if a specific food company set out to, hypothetically, source all their meat, eggs, or milk from farms that only use, say, sustainably-grown feed, this would significantly limit the flexibility livestock growers have to source the cheapest feed they can. This would, without doubt, cause the price of this animal protein to skyrocket (which for our commodity burger brand famous for its “value menu,” is probably not going to fit the business model-- but more on this in a moment).

The bottom line here: food companies often can’t meaningful know (or even guess) what exactly is being fed to the livestock which will eventually become the animal protein in their supply chains. Without visibility into these animals’ diet, they certainly can’t identify the acres where this feed is grown, and therefore I’m not sure how they could do anything about the farming practices that occur there.

But! I’m willing to consider that a food company could be so motivated to do The Right Thing that they’re willing to do this work inside their own supply chains, by attempting to source animal protein that’s been fed forage or grain that was raised more sustainably/regeneratively. But beyond altruism, let’s think about the conditions that would need to exist for a company to take this route.

What incentive do consumer-facing food companies (like McDonalds) have to impact what their meat eats?

A thing that’s often assumed about “the food system” is that big, rich, powerful companies have unconditional control over smaller companies in their supply chains- that the McDonalds’ of the world could change every cattle farm tomorrow, if they really wanted to.

The reality is, even the biggest and most powerful companies primarily have a single lever to enforce their will on their supply chain partners— price. As in, the price they’re willing to pay for the ingredients they need. Therefore, since food companies cannot force their suppliers to sell them inputs at a loss (at least, not for long), they must be willing to pay a premium for more expensively-raised animal protein.

The problem is, companies generally don’t become multi-national convenience food giants by paying a premium for the ingredients they buy. On the contrary, they make money by widening the gap between the price they pay for ingredients and the price at which they sell their final products. The whole game is turning low-value constituents into high-value finished goods.

Since, making demands about the way livestock is fed is going to increase a food company’s costs, the very least a company would need to justify this move is (effectively) a guarantee that their customers are going to more than compensate them for the new expense. Food consumers are not willing to do this. The vast majority of people are motivated by exactly two things: price and taste. Most are not going to pay more for “regeneratively grain-fed beef.”

Even amongst the more spendy “some” who might pay more, these consumer are looking for exactly what you suggest above, even more costly claims like “grass-fed.” But, the higher-end consumer looking for this kind of label is just way less likely to be buying drive-thru hamburgers than their more price-motivated contemporaries. In other words, as a product, “regeneratively-grain fed” or “grass-fed” McDonalds burgers just... they don’t make that much sense for the business.

This, in short, is why companies are much more excited about what I suggested above, about setting up on-farm pilot projects and one-off sustainability programs outside of their supply chains, than they are about actually sourcing “regen” or “sustainable” products within their supply chains. Because to do this work within their own supply chain will necessarily raise their own the costs, which will in turn fuck up the fundamental accounting of their business. Therefore, most food companies do not have a meaningful incentive to try and effect animal feed, and in fact are largely discouraged from even trying, because they risk raising their own input prices and suffering financially for it.

But! Again, what if America’s favorite burger chain decided it didn’t care about the cost and that it was desperate to effect the “animal feed” cropland acres that sit at the very far end of their supply chain. Could they even do it?

What power do these companies have to impact this feed?

I would argue that no, they couldn’t, because they are quite simply too far from those acres to meaningfully influence them.

To explain how this distance weakens a food company’s power, let’s set a McDonalds-type company aside for a minute. Let’s instead explore a couple of different examples in beef’s adjacent world, dairy. Dairy is interesting because it is arguably the part of the livestock sector where food companies sit closest to the “animal feed” cropland acres in their supply chains.

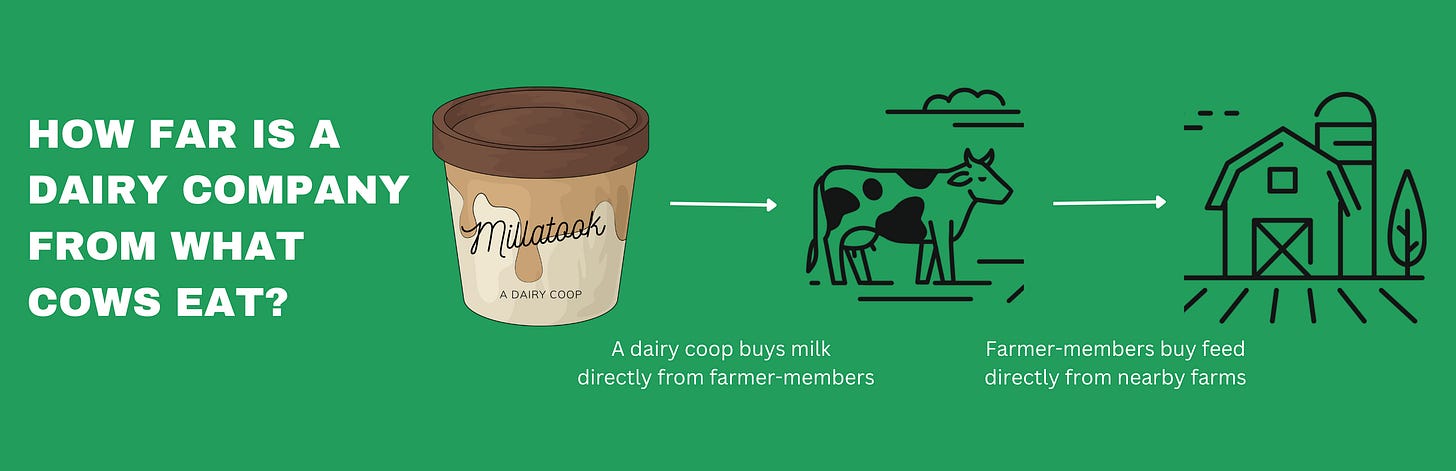

Consider a food company with quite a short supply chain, like a farmer-owned dairy coop:

This is about as close as a food company could be to the cropland acres that go into animal feed in their supply chain. In this example, it is reasonable that the consumer-facing coop might be able to influence it’s farmer-members to seek out (and pay a premium for) more sustainably- or regeneratively-grown livestock feed. This is true because it is possible to pass value back through this short chain, and its not insanely costly to verify that products passed along the chain in the other direction meet the standards that are being paid for. In other words, to make a regenerative dairy claim on tubs of retail ice cream, the farmer-owners of the coop would have appropriate incentives and ability to verify the provenance of their feed with their direct feed suppliers. Then, the food brand can sell the ice cream at a premium, and pass a portion to farmer-owners, who can in turn afford the premium on more regeneratively-grown feed.

But beyond this kind of ultra-short supply chain where food companies have intimate relationships with their farmer-suppliers, things get trickier.

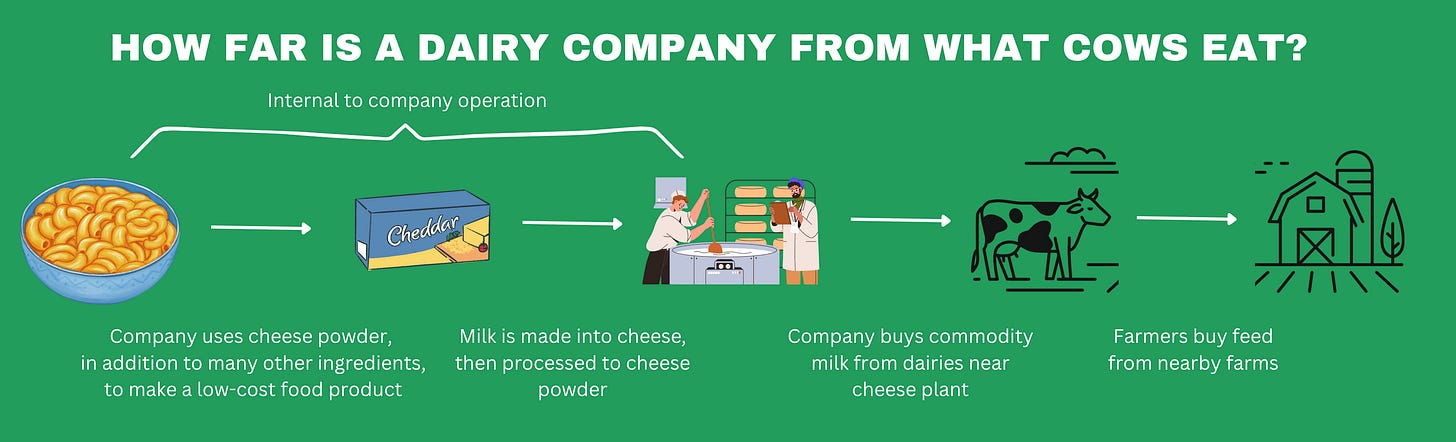

Consider a hypothetical boxed mac and cheese manufacturer:

This graphic represents the simplified supply chain of one major boxed mac and cheese manufacturer in the U.S. However, because boxed mac and cheese, like most of the other dairy products in this company’s portfolio, are low-cost and because the company does so much to process the milk after it’s been purchased (transforming the commodity input from milk to cheese, than cheese to powder, than powder to consumer product), their incentive to pay a premium for their milk is extremely limited. In fact, this kind of company is likely unable to bump up their price considerably to accommodate a premium milk product, because it could dramatically decrease sales. In fact, they’re much more likely to demand lower-cost milk than to offer an extra incentive just because cattle were fed regeneratively-grown hay or silage.

Boxed mac and cheese might seem obscure, but a very similar set of motivations is playing out across major dairy food brands. Whether a brand needs millions of gallons of milk to make coffee drinks or countless single-serving containers of cream cheese to serve with their bagels, companies generally get further away from the farms where their ingredients come from as they get larger, and their power to make demands on those farms declines as well.***

This boxed mac and cheese company contracts directly with a coop, so at least they know their milk is sourced from among a certain group of farmers, but those are just the dairymen, and not necessarily the farmers that grow the feed. And many other companies buying dairy products (including ingredients like powdered milk), rather than fluid milk, don’t even have that level of visibility to where their product originated. The feed-growing farmers are almost impossible, from the food company’s position in the chain, to identify.

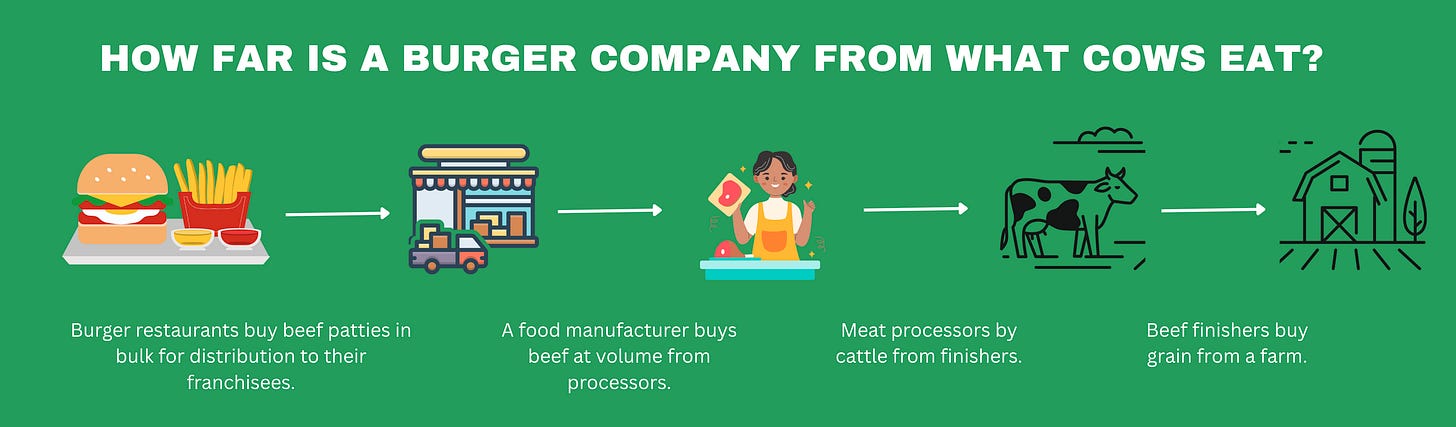

This brings us all the way back to a McDonalds-type restaurant and the beef they source for their burgers. Your average fast food burger chain is even farther from the “animal feed” acres than the boxed mac and cheese folks.

This is because burger chains like McDonalds don’t buy cattle from farmers. They don’t even buy cuts of meat from meat processors. They buy finished burger patties from food manufacturers. This means that if they were to somehow try and influence the cropland acres at the far end of the supply chain-- they’d have to work back through at least three whole sectors (from the manufacturers to the processors, then to the cattle raisers, and only then to the feed producers). And at each one of those steps-- the number of companies and individuals involved multiplies exponentially.**** I don’t know that there is a fast food burger chain in existence that has the resources to have an impact this vast and this deep in their supply chain. It would, I think, essentially require the company to remake the American protein system from scratch.

In the case of McDonalds in particular, the reason I don’t expect them to attempt this work is because they don’t really buy beef that’s fed from American cropland anyways. McDonalds sources patties made almost exclusively of imported lean trim, an 80/20 blend of ground beef. It’s super cheap and appeals to their customer’s taste buds, but it’s not raised in the U.S., and the cows that make it probably don’t eat American-grown crops either.****

Another way to think about this distance is through an analogy. Set protein aside for a minute, and imagine instead that I am a baker, and I want to effect change in the food system, so I insist that wheat farmers I work with prove to me that the conditions in the Moroccan mines where their potash comes from are humane and environmentally-friendly. First of all, farmers wouldn't know where to begin to access that information, and most probably wouldn’t be able to retrieve it even if they did. That's similar to the idea that an individual food company, even one as big as McDonalds, could tell their meat-buyers that they want to know how their animal feed was grown. The food company is simply too distant from that link in the supply chain to exert this level of influence.

Maybe this all seems lame, like the long and convoluted nature of modern supply chains are providing an excuse for food companies to not even try to make the ingredients they buy better for the environment.

And, yes! That’s true! This was the point I was trying to make in the original piece. Food companies do not have the right leverage to motivate change on animal feed (or almost any) farmland acres. They are too distant from them in their supply chains and they buy too few of the products of these landscapes. This is not to excuse food companies of their harms and excesses, but to point out that we can flip the “food company” switch all we want, it’s just not the one that’s controlling how crops are grown.

But before we wrap up, I want to address one other part of this discussion, which is that maybe one way to snip the end off these supply chains is to just make “grass-fed” the standard, and thus remove all those grain and oilseed “feed” acres from the equation altogether.

Isn’t grass-fed the right alternative?

Setting aside the question of grass-fed beef’s ecological benefits for a moment, I want to refocus on food companies and their ability to influence American farmland.

The difficult reality is, even if a company like McDonalds was willing to overlook their lack of information, ignore its own incentives, say ‘fuck you’ to their customers, and insisted on stocking grass-fed beef only, this is likely to have a negligible impact on “animal feed” cropland acres in America, the ones we originally set out to explore.

The reason for this starts with the definition of grass-fed cattle, which says that animals must eat only grass and forage throughout their lifetime, and “cannot be fed grain or grain byproducts, and must have continuous access to pasture during the growing season.” That means that to demand more grass-fed beef is to largely opt-out of the supply chain for cropland products.***** But being a part of the supply chain is how companies exert their power. Therefore, for a protein company to move towards grass-fed products is to weaken whatever influence they might have on cropland.

The rational followup here is to ask, well, shouldn’t more demand for grass-fed beef reduce the demand for feed and thus reduce the number of acres going to say, corn and soybeans? The answer is, frankly, no. Because all these crops have a lot of other applications beyond feeding animals (i.e. biofuels, industrial applications, exports) and therefore a reduction in feed usage will simply lead to more grain and oilseeds being used by other sectors. Therefore, even if we cut feed demand by, say, 20%, that might have only a tiny impact on how much grain and oilseed is grown, because farmers will likely plan to keep growing those crops for other uses.

Don’t get me wrong, I think extensifying protein production by doing things like restoring midwestern grass prairies and feeding cows on living plants rather than intensively in barns and lots, would lead to a lot of environmental benefits. But highly intensive livestock production is currently the cheapest way to grow animal protein (because, of course, the environmental cost is externalized). If food companies tried to encourage extensification, they'd once again be opting to raise the price of their own inputs, which they are just deeply unlikely to do.

All to say yes, there certainly are other things that livestock feed acres could produce that would contribute to healthier land and people. Pulses, native vegetation, trees, and low-cost housing come to mind, and those are just off the top of my head. But food companies don't have any way to motivate farmers or ranchers to make this transitions. They don't have the resources or the influence.

So then how do we change “animal feed” acres?

Many food system advocates will tell you that we need to reduce the grain and oilseed monocropping— much of which goes to livestock feed— that occurs across so much American farmland if we want to see better environmental and human health outcomes. For years, these advocates have pressured food companies to abandon corn and soybean ingredients (including, to some extent, grain-fed protein) as a way to effect this change. And for all those years of effort, in 2025 we’re looking to harvest largest corn crop ever grown in the U.S. in just a few weeks.

In other words, despite all the activism, the ethical consumerism, the alarming reports, the impact investments, and the corporate food company commitments, the system is moving directly opposite to all those efforts.

But despite this epic failure, so many in this space are still obsessed with putting food companies at the center of this work. Why? I think it’s a mindset issue.

See, in my years of doing this work, the most enduring mindset that I encounter is the belief that the American consumer has the power to change the food system. This is because each of us participates in it, often multiple times a day, and therefore we want to believe that we, by way of the food companies we patronize, have power over the agriculture system that occupies 60+% of our nation.

In other words, I think, we desperately want to be able to vote with our forks, and that by doing so, we can be the force for change we crave.

But if you take away anything from reading all this, let it that voting with our forks doesn’t work. Consumers, non-profits, even activist investors do not have the market power to browbeat a multi-billion dollar burger chain, or anyone else, into doing something they simply don’t have the power or incentive to do. And if we continue spending all our time and energy make these companies “commit” to making changes we know they can’t make, we only have ourselves to blame for the lack of progress.

There is a single entity in our food system with the actual power to make changes all throughout the system, be it on farm, amongst processors and manufacturers, or within food companies. It’s the government. The federal government has the power to set the standards for beef quality (as they did in the aftermath of The Jungle), to force food companies to pay for the consequences of the products they serve, and even to decide how animal feed can (and can’t) be grown. And the great news about the government is, we can vote for those folks with our actual votes (no forks required).

No food company is going to take these kinds of action on their own, and expecting them to step up to this enormous plate will not only lead to disappointment— it’s a recipe for disaster.

*You might be reasonably wonder then, how did I get the number that I used in the original graphic? Animal feed usage is calculated by the USDA as a category called “feed and residual,” which the department uses as the sort of catch-all. When USDA economists can’t account for a spare million bushels of corn, it’s just assumed that they must have gone to feed an animal somewhere. All to say, the “Animal Feed” acre number I used above isn’t finely calculated, it is more accurately the number of acres that are left over after we’ve determined how all the rest were used.

** Famously, McDonalds has done exactly this. It has invested in sustainable beef pilot projects, but notably, these sustainable beeves do not become meat sold at McDonalds restaurants. Like many other pilot sustainability projects in agriculture, the company has created a situation where they’re basically doing agricultural philanthropy, rather than actually “cleaning up their own supply chain.” (More on why this is later.)

***Not to mention that for many of these companies, the animal protein they source is not the “product” that they’re customers are clamoring for. A brand like Panera is probably not going to sell more bagels or bread because the free dairy spread that comes in the bag is regenerative. A brand like Starbucks is probably not going to sell more coffee because the half-and-half next to the napkins is grass-fed.

****This is because, for example, a food manufacturer is likely buying its meat from one or more processors, who are in turn buying their cattle from hundreds if not thousands of individual cattle-raisers, who each might be buying some feed and growing some feed, possibly from multiple different sources.

*****And that’s not to mention that most of the beef from these cattle goes to some other use.

*****There is a caveat here. Hay and alfalfa are included in “cropland acres” as is “cropland pasture.” However, it is safe to assume that much of the hay and alfalfa harvested in the U.S. does not contribute to grass-fed production, primarily because grain-fed production is just more cost-effective.

"voting with our forks doesn’t work. Consumers, non-profits, even activist investors do not have the market power to browbeat a multi-billion dollar burger chain, or anyone else, into doing something they simply don’t have the power or incentive to do. And if we continue spending all our time and energy make these companies “commit” to making changes we know they can’t make, we only have ourselves to blame for the lack of progress." Agreed Sarah!

I have repeatedly made the point that the notion that the consumer is in command is nonsensical, even in much simpler settings than the globalized food system. A few months ago I wrote: "The globalization of trade has given the wealthier share of the global population the impression that you can eat what you want. This fits well with the neoliberal ideology that portrays capitalism as democratic where people “vote with their wallets”. But it is an illusion - even for the rich countries. Rather than putting our faith in green consumerism we should strive to de-commodify food. " https://gardenearth.substack.com/p/the-consumer-power-myth

Glad you turned on paid subscription.

Everyone should eagerly pay for quality.