Got to Have a Code

Feeling grounded in the 21st century

Programming Note: News (Part 1) after today’s essay.

Growing up, my mom read a lot of self-help books.

You’d think that would have given me a better impression of them, but it didn’t. I’d internalized the “bootstraps” narrative too completely. Consciously or unconsciously, I thought that people shouldn’t need books to figure out how to help themselves.

Isn’t that fucked up?

There’s a good book about American called The Way We Never Were. It was written decades ago, but its analysis of historical tropes is really helpful. It looks at every part of the individual, family, and society– from housewives to “welfare queens,” from distant fathers to guileless children, and explores the Norman Rockwell painting of it all to show that the idealization we’ve created of the past is simply not true.

There’s a single piece of data in this book that always stood out to me– that between 1900 and the 1990s, the number of Americans who would describe themselves as “a person who lives by a code” dropped by more than 50%. Before, during, and immediately after the world wars, the average American believed that yes, they lived their life by a certain set of purposeful rules. But by the end of the century, it was the rare American, one in ten or so, who felt the same.

Maybe it’s easy to attribute this directly to a decline in religiosity. After all, aren’t the commandments, covenants, or words of a given deity the main kind of “code” people follow? Love thy neighbor as thyself. That’s a code. There is no god but God, and Mohammed is his prophet. That one too. Follow these guidelines, fulfill your Dharma. Makes sense.

When I hear the word “code,” I go straight to, “man’s gotta have a code.” That’s Omar, from The Wire. Omar’s code had three parts:

“never put a gun on no citizen”

“man’s gotta have a code”

“church Sundays.”

In other words, non-violence towards the innocent, respect towards the ethics of others, and honoring sanctity. I’d argue that that’s as good a code as any religion’s. Simpler too.

Because my mom read so many self-help books, she loved an affirmation. She was always writing herself notes and leaving them tucked in the corner of mirrors, perched on her bedside table, or stuck on the fridge. They were supposed to be little reminders of who she wanted to be and what she wanted to achieve. They were always very carefully worded (“don’t write ‘don’t forget’” she’d tell us, “write, ‘remember’”) and they varied from the mundane to the sublime– from “skinny women don’t snack” to “I am lovable and loved.”

Of all the self-help ideas, the habit of writing notes to myself was one I liked. Admittedly, I usually wasn’t trying to brainwash myself into health, wealth, and happiness– I was just trying to be nice to myself, maybe correct a little of my negative self-talk.

The habit petered out by the time I went to college, but once, in my young adulthood, I saw where a friend had written all her big goals and dreams on sticky notes, and put them up on her wall for a while. I liked the idea, so I copied it. After a while, I took all the sticky notes down and put them in a notebook– tired of staring at dreams that felt so far away.

But possessed by some angel or devil, I pulled out one last sticky note, carved three words onto it, and stuck it to the top of my bedroom mirror. It wasn’t quite a dream or a goal, it wasn’t quite an affirmation. It wasn’t even something I wanted to remember, because it was not something I could forget. But it felt right to see it up there, floating above my head every day, like a label, or a thought bubble.

It said, “People above all.”

Another kind of code is the old Irish folkloric tradition of geas or geis. A geis is something between a gift and a curse— a lifelong obligation that can be a source of great power, or doom. A warrior hero might have a geis that they must lend help to anyone who asks for it, or to touch the feet of any old woman who passed him by. There is usually some profound reason for a geis, a particular situation that led to its assignment. To fulfill a geis is to have access to immense spiritual power, and to fail to fulfill a geis is a death sentence.

Perhaps most famously, Cú Chulainn, the Hound of Ulster, a demi-god of Irish folklore, was felled by competing geases. His first geis was that he could never eat dog meat. It’s because he’d killed a dog that was attacking him in his youth, a crime which he made right by offering to take the animal’s place as guard of a great house until a replacement could be had (hence the nickname, Hound or “Cu”). This act brought about the geis, since eating dog meat for this hero would represent a sort of spiritual cannibalism. But he was also party to the competing geis that he must always accept hospitality. One day, when a host offered him a meal of dog meat, he became caught in a geases-fueled death loop. He was spiritually weakened, and a short time later, he died.

That’s an important characteristic of a true code– strengths and weaknesses must flow from the same source. Consider the entreaty to love thy neighbor as thyself. It’s a nice idea sure, but it’s also flawed. Think of how badly we often treat ourselves. Think of how little self-love there is in the world. It reminds me of the famous Olive Garden code or geis, “When you’re here, you’re family.” I mean, love them as I might, my family and I often treat each other worse than we would ever treat someone who wasn’t a blood relative. (Maybe that’s why I don’t feel the call of bottomless breadsticks– it’s not worth the risk that they might, as they threaten, treat me like family.)

Like an old fashion geis, it wasn’t me who came up with the code, “People above all.” It was an old roommate, one day when we were talking about friendship and sacrifice– what it really means to be there for someone and what it means to fail one another. Having faced those consequences before had surely shaped my level of urgency around the issue, and I knew first hand that being a good friend is not simply a nice title. It can be a matter of life and death.

“You can tell,” my friend told me in response. “But it’s also more than that. I can tell that you know how much a person is worth.” She paused, trying to explain. “Because you do not hesitate. It’s clear that there is nothing you value more than people.”

This is my code. In all its imperfect glory. People above all.

It’s been eight or ten years since I wrote those three words on the sticky note, and I still have that little Kraft single of paper. The stick is long gone from the back– it’s now affixed to my work computer with scotch tape. The ink has faded away too, and the original yellow of the note. Today it’s kind of an off-gray color, and I’ve retraced the words with a red pen. But I still look at it everyday, and I think about what I’m doing today for the people in my life. I look at it when someone asks to do a work call at a time that conflicts with meeting up with a friend. I look at it when I think about responding harshly to a mean comment. And I look at it when I write. And then I say no to the call, I rethink my responses, and I do my best to write from my heart instead. Like a person.

And I’ll be the first to admit that this code is far from perfect. Many companions have challenged the human-centricity of it. “What about animals?” people ask. “What about plants? What about ecosystems? What about other life and life elsewhere?” It’s a flavor of bigotry, I suppose, to prize people more highly than anything else. I can’t deny that, and I don’t defend it with the idea that man was meant to have dominion over the earth (or whatever). My only defense is, well, I am a person, and a flawed one. I’d like to embody a selfless, god-like love for all life and existence, but I don’t. I’m both too selfish and too limited for that. I only have however many years on this earth, and the best of my experiences in this life have been with people. I love them. That’s all there is to it.

The reason The Way We Never Were talks about living by a code is in because doing so correlates pretty well with happiness and life satisfaction. Omar was onto something, and a man doesn’t just need a code, he wants one. Whether we recognize it or not, having a code is part of having a good life. It’s something to believe in.

A code doesn’t have to be perfect. In fact, most good codes are flawed. They leave us exposed to certain kinds of weakness, even as they empower us with untold strengths, the kind of strength that comes from knowing oneself. Whether we get our codes from a religion, from a spiritual practice, from a TV show, or from inside ourselves, it doesn’t matter. Adopting a code, and holding ourselves to it as best we can, is an incredibly powerful and grounding act. It is an antidote to external uncertainty, a tonic to soothe the pain of navigating an unpredictable and threatening world.

No matter what happens, no one can take your code from you. Only you can do that. That is one of its gifts too. Adopting a code is one of the few ways that we truly and individually help ourselves. It is an internal covenant, a fortification from within, the selection of a path and a purpose, and a commitment to not turning back.

We stand in a historical moment when having a code is more important than ever. A code is a compass in a storm, an inextinguishable candle flame in a hurricane. And one of the great things about a code is that they don’t require any big production. You don’t need an old Irish witch to assign it to you, or to pay a guru and sweep an ashram floor for a decade to get a mantra. You don’t have to fast, pray, and wander in the desert for forty days. You can just think of it, and say, “yeah, that’s my code.” That’s all it takes.

If you want to put a little ritual around it, I’m a big fan of the sacred sticky note. Maybe you need a few (Omar would). Maybe put them up where you can see them every day. I liked having it on my mirror. I feel like it subliminally helps my brain associate my own face with the idea of who I am, for those days when things happen that make me uncertain.

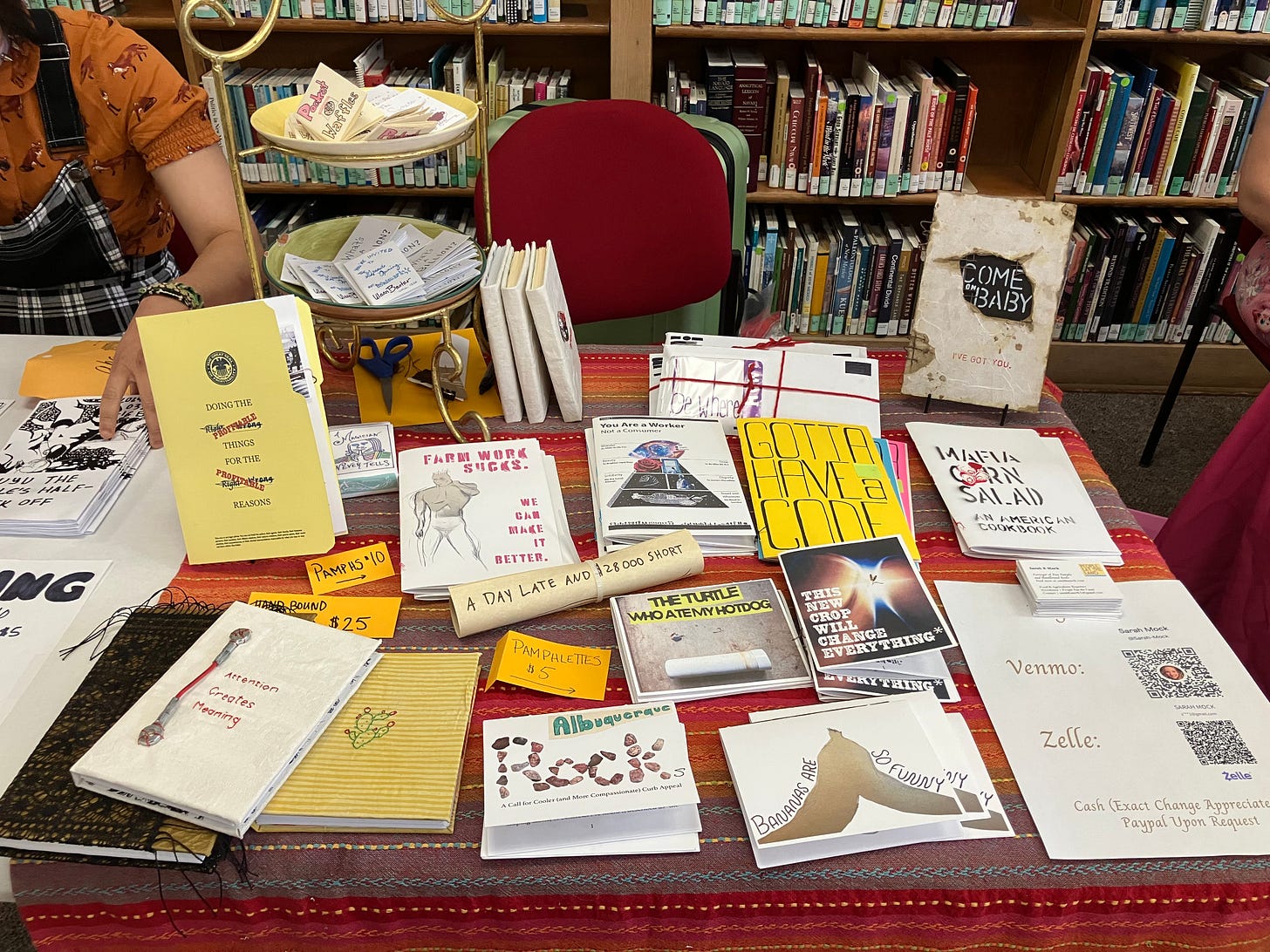

Thanks for reading. So my first bit of news is— I exhibited at the Albuquerque Zine Fest this weekend! It was a blast, and so cool to be out in the wild, sitting behind a table full of essays (some of which I’ve shared with all of you here), and seeing which ones people reached for and were excited about. I had a ton of great conversations about agriculture, food, landscaping, and writing, and I sold things! Wild! For folks who ordered copies of MAFIA CORN SALAD earlier this year, your support and encouragement was a big part of what got me here— so thank you all again so much.

I’m also going to be making these pamphs, pamphlites, pamphlets, and pamplitos (and hand bound journals!) available to all of you. Have you wanted to share something you’ve read here with someone, but are sure they’ll never read a forwarded email? Or do you just want to own a physical and artsy version of one of the essays from this year, including this one? Or are you looking for more writing that’s never been (and never will be) available online? I will have a store set up in the next week or so, and will link it in the next newsletter. I’ll also be featuring individual pamphs in each newsletter for the next few months, so look out for that.

In the meantime, here’s a preview— my table from the fest:

Before sticky notes I had little cards stuck in the corner of the mirror. Many ended up as book marks. I find them all the time. Refrigerator magnets also.

My grandchildren gave me a Ball jar full of their own "words of wisdom". I guess the habit has been passed along.

Like your Mom, I read all the self help books. Now I am reading stories about people who survived the Holocaust, looking for the glue that kept them from exploding. ....

. "People Over All".....covers a lot of ground....I am going to stick that up. It may imprint on me as it has on you and become a new beacon of Light.

Thanks for sharing your journey! 🩷